Asteroids From The Dawn Of The Solar System Discovered

Aug. 04, 2017 Jonathan O'Callaghan

Scientists say they have found a group of asteroids left over from the earliest days of the Solar System. These may finally help us work out how planets formed.

The discovery, published in Science, was led by Marco Delbo from the Côte d'Azur Observatory (OCA) in Nice, France. Using data from NASA’s WISE satellite in orbit, they studied various groups of asteroids located in the main belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Most asteroids belong to families. That means they formed from the same original rock long ago, perhaps when two asteroids smashed together. The resultant asteroid fragments then formed a noticeable V shape in space.

However, Delbo and his colleagues managed to find 17 dark asteroids that did not belong to such a family. This means they were very likely born from the protoplanetary disk of dust and gas that orbited our Sun about 4 billion years ago, forming into so-called planetesimals, the building blocks of planets.

“These asteroids cannot be fragments of other asteroids,” Delbo told IFLScience. “So they must have formed in a different way, and the only mechanism is that they were created from the protoplanetary disk.”

These 17 asteroids were located between a distance of 2.2 and 2.33 AU from the Sun (1 AU, astronomical unit, is the Sun-Earth distance). The main belt itself spans 2.2 to 3.5 AU, so these represent a small cross section of the whole belt. It’s hoped that, in the future, the rest of the belt can be examined in a similar way.

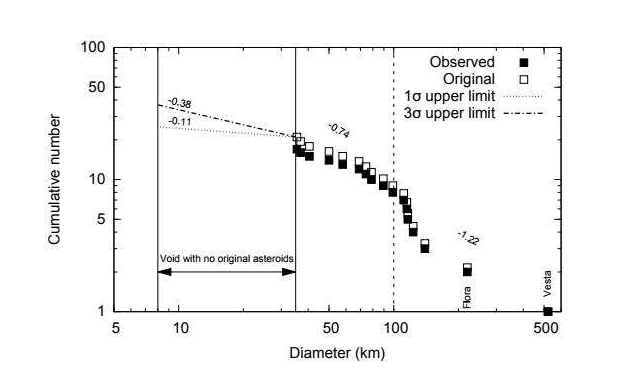

The sizes of planetesimals discovered so far. Delbo et al.

Note that these are not the first primordial asteroids we’ve discovered. The large asteroids Ceres and Vesta, for example, are thought to be planetesimals of sorts. However, these newly identified 17 asteroids are important because of their smaller size, no less than 35 kilometers (22 miles) across.

“We know the big guys should form, but we don’t know how many small ones can form,” said Delbo. “Our work provides the first observational constraint.”

This should help us refine our theories of planet formation. Basically, there are two trains of thought. One is that planets grow when small planetesimals join together. The other is that a single large body sweeps up pebble-sized rocks from the protoplanetary disk.

While this study does not specifically tell us which theory is correct, it does get us closer to an answer. We really need to understand more about the first population of asteroids, so finding as many as possible is a pretty good idea.

“We need to know how large the largest first asteroids were and how efficient they were at forming from dust,” co-author Kevin Walsh, from the Southwest Research Institute in Texas, told IFLScience. “This work should help modelers better understand their models of asteroid and planetesimal formation.”

Latest News

More...